Identical twins begin life with virtually the same DNA. They share the same genetic inheritance, the same starting blueprint. Yet as they age, they often develop different health conditions, respond differently to the same environments, and can even develop distinct health outcomes and traits.

If their genetic code is so similar, what drives these differences? You might be thinking, "Of course they're different... they're making their own choices, eating different foods, living separate lives." And you're right. But what most people don't consider is how those choices and experiences translate into biological differences at the molecular level. The answer is epigenetics.

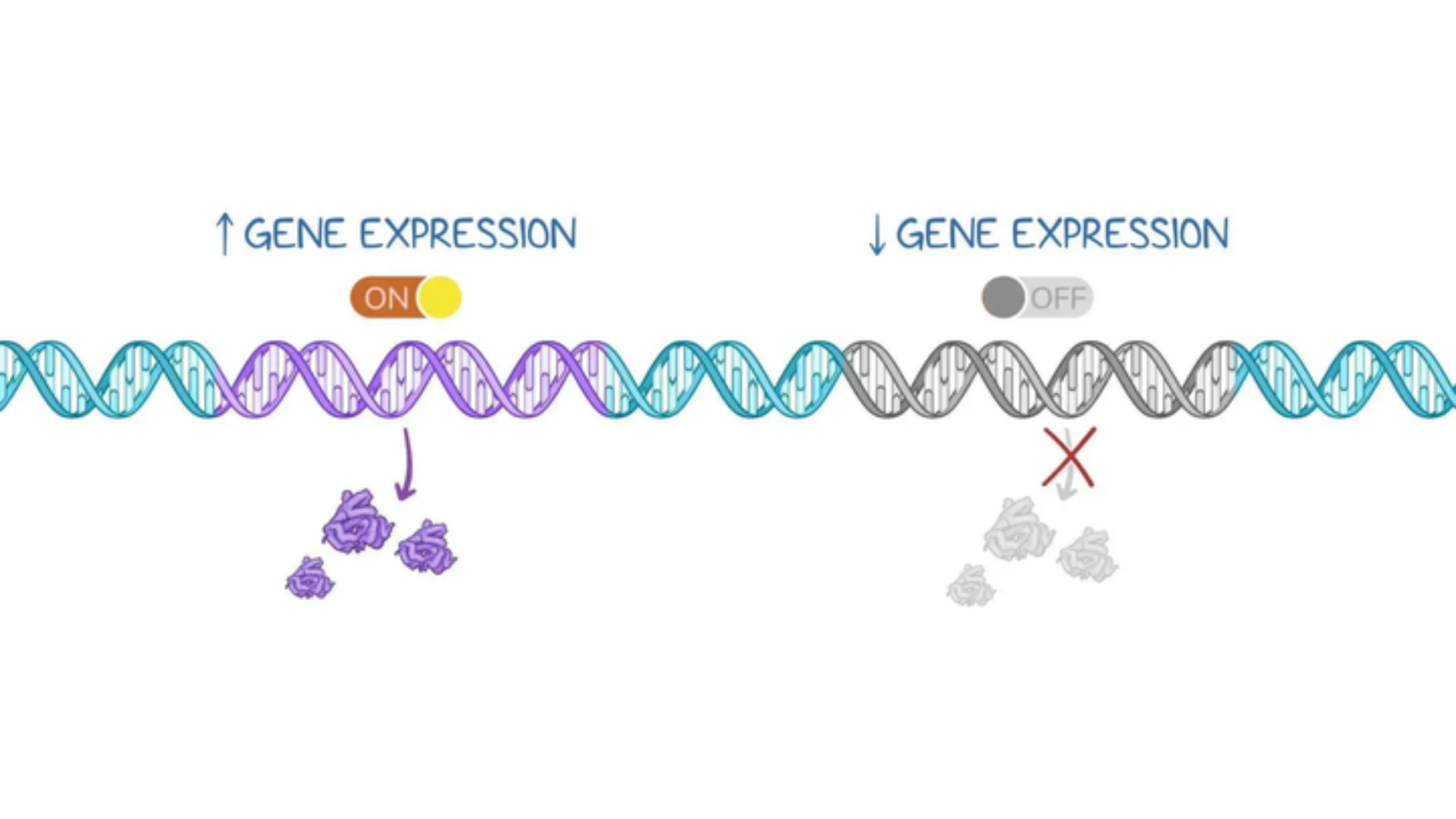

Epigenetics is the study of how chemical modifications control which genes are turned on or off without changing the DNA sequence itself. While twins start with nearly identical genes, the expression of those genes diverges over time. Environment, experiences, lifestyle choices, and even random chance create different epigenetic patterns.

Understanding epigenetics reveals something profound: even though two people might have nearly identical genes, they can end up biologically very different. There's a flexible layer sitting between your DNA and your actual biology. That layer is where your environment and daily choices have their impact.

Your DNA contains roughly 20,000 to 25,000 genes (instructions for making proteins that determine everything from your eye color to how your cells produce energy). But not all genes are active all the time. A liver cell and a brain cell contain identical DNA, yet they function completely differently because different genes are expressed.

Epigenetics is the system of chemical modifications that controls which genes are turned on or off without altering the DNA sequence itself. Think of your DNA as hardware and epigenetics as software. The hardware stays the same, but the software determines how it operates.

These epigenetic marks act like volume controls on your genes. They don't change what the genes say, but they control how loudly those genetic instructions are read.

DNA Methylation

This is the addition of methyl groups (small chemical tags) to your DNA. Methylation happens primarily at CpG sites, locations where two specific DNA building blocks (cytosine and guanine) sit next to each other. These tags often get added within or near promoter regions (the on/off switches that control whether a gene gets used). When methylation happens at these control switches, it typically silences that gene.

Histone Modifications

DNA wraps tightly around spool-like proteins called histones. Chemical changes to these histones (such as acetylation) determine how tightly or loosely the DNA is wound. Tightly wound DNA is inaccessible, so those genes stay silent. Loosely wound DNA is accessible, so genes can be read and used.

Non-Coding RNAs

Some RNA molecules don't make proteins but instead act as regulators. They can block the messenger molecules (mRNA) that carry instructions to make proteins, or recruit other molecules that turn genes off. These non-coding RNAs add another layer of control over which genetic instructions get carried out.

Together, these mechanisms create the epigenome (the complete set of epigenetic marks across your DNA that determines your pattern of gene expression).

Nutrition

What you eat provides building blocks for epigenetic modifications. DNA methylation requires methyl donor nutrients including folate (leafy greens and beans), vitamin B12 (animal products), and choline (eggs and meat). These nutrients support the one-carbon metabolism pathway, which is the biochemical assembly line your body uses to create those methyl group tags.

Other dietary compounds have also been shown to influence epigenetic processes. Polyphenols (beneficial plant compounds in colorful fruits, vegetables, tea, and coffee), omega-3 fatty acids (from fish and nuts), and various vitamins and minerals all affect which genes get turned on or off.

Stress

Chronic psychological stress has been shown to affect epigenetic patterns, particularly in genes related to stress response, inflammation, and mood regulation. Studies show that childhood trauma can leave lasting epigenetic marks. For example, researchers have found changes in the glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1), which helps your body respond to stress hormones. These changes can influence stress reactivity, immune function, and mental health decades later.

Physical Activity

Exercise has been shown to influence epigenetic patterns in multiple tissues. Physical activity affects methylation of genes involved in metabolism, inflammation, and cellular energy production. This means exercise can literally change which genes are active in your muscles, fat tissue, and other organs, helping explain why regular activity has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity, reduce inflammation, and provide cardiovascular benefits beyond just calories burned.

Sleep

Sleep quality and circadian disruption have been shown to affect epigenetic regulation. Genes involved in metabolism, immune function, and cellular repair show altered methylation patterns with chronic sleep deprivation.

Environmental Exposures

Toxins, pollutants, and chemicals can alter epigenetic marks. Research indicates that exposure during developmental windows can create epigenetic changes that persist for years, which is why environmental exposures during pregnancy or early childhood can have lasting health effects.

Social Environment

Social relationships and environment have been shown to influence epigenetics. Studies show that social isolation, chronic stress, and socioeconomic status correlate with distinct epigenetic patterns. Factors like poverty, discrimination, or chronic stress can leave molecular marks that affect gene expression.

Some epigenetic marks have been shown to be passed from parent to offspring, allowing environmental effects to influence the next generation.

The Dutch Hunger Winter of 1944 to 1945 provides a striking example. Children born to mothers who experienced severe famine during pregnancy showed altered methylation patterns decades later. More remarkably, their grandchildren (who never experienced famine themselves) also showed epigenetic differences and increased rates of metabolic disease.

Some evidence suggests certain epigenetic changes may persist across generations, though the extent of true transgenerational inheritance in humans remains under investigation. This raises questions about how experiences your parents or grandparents went through might affect your health through changes in gene expression patterns.

Disease Development

Many diseases have been shown to involve epigenetic components. Cancer often results from both genetic mutations and abnormal epigenetic changes. Metabolic diseases, cardiovascular conditions, and neurological disorders all show altered epigenetic patterns.

Aging

Epigenetic patterns change predictably with age. Beyond marking biological age, research suggests these changes may contribute to aging itself. As cells accumulate epigenetic changes, some genes that should be active get silenced while others that should stay quiet become active, contributing to age-related cellular dysfunction.

Personalized Medicine

Everyone's epigenome is unique and shaped by life experiences and environment. Two people with the same genetic variant may experience different outcomes depending on how epigenetic regulation modifies that gene's activity. This helps explain why genetic risk doesn't always translate to disease.

Perhaps the most important aspect of epigenetics is what it means for your agency over health. Unlike DNA sequence (which you inherit and cannot change), epigenetic patterns are modifiable.

While you can't control the genes you inherit, epigenetics provides hope because you can influence how those genes are expressed. The lifestyle factors that affect epigenetics (nutrition, stress management, exercise, sleep) are areas where you have at least some control.

This doesn't mean everything is within your control or that you can overcome any genetic predisposition through lifestyle alone. Genetics still matters enormously. But epigenetics reveals that the relationship between genes and health outcomes isn't deterministic. There's space for intervention, for prevention, for positive change.

Epigenetics represents a fundamental shift in how we understand the relationship between genes, environment, and health. Your genome isn't a fixed instruction manual but a responsive system that integrates signals from your environment.

Every dietary choice, stressor, or period of recovery. Every night of sleep, every moment of physical activity. These aren't just affecting how you feel in the moment. They're interacting with molecular processes that control which genes are active, potentially influencing your biology in lasting ways.

Understanding that your genes are listening to your environment offers a powerful framework for thinking about health. The choices available to you matter at the molecular level, written in chemical marks across your genome that help determine which genetic potential becomes biological reality.

More Info: At WellPro, we’re building an AI-native clinical platform purpose-built to scale the next era of care: personalized, preventative, and data-driven. Our thesis is simple but bold; the future of care delivery will be patient-centered, proactive, longitudinal, and closed-loop. That demands infrastructure that can ingest multi-modal health data, generate insight, drive action, and continuously optimize based on outcomes.

We believe Agentic AI is central to making this vision real. Not just chat interfaces or “co-pilots,” but deeply embedded, goal-driven AI agents that operate within the clinical system itself, helping surface insights at the point of care, automate routine tasks, and ensure closed-loop follow-through on interventions.