You doom scroll through social media even though you're not enjoying it. You chase a promotion you're not sure will make you happy. You reach for another cookie despite knowing you'll feel sluggish afterwards. You achieve something you worked incredibly hard for, only to feel... nothing?

There's a specific reason this can happen, and many times it's not about willpower or character. Your brain has a fascinating quirk: the system that makes you want something is completely separate from the system that makes you like it. This is controlled by a small but powerful brain structure called the nucleus accumbens, which creates a fundamental split between chasing rewards and actually enjoying them.

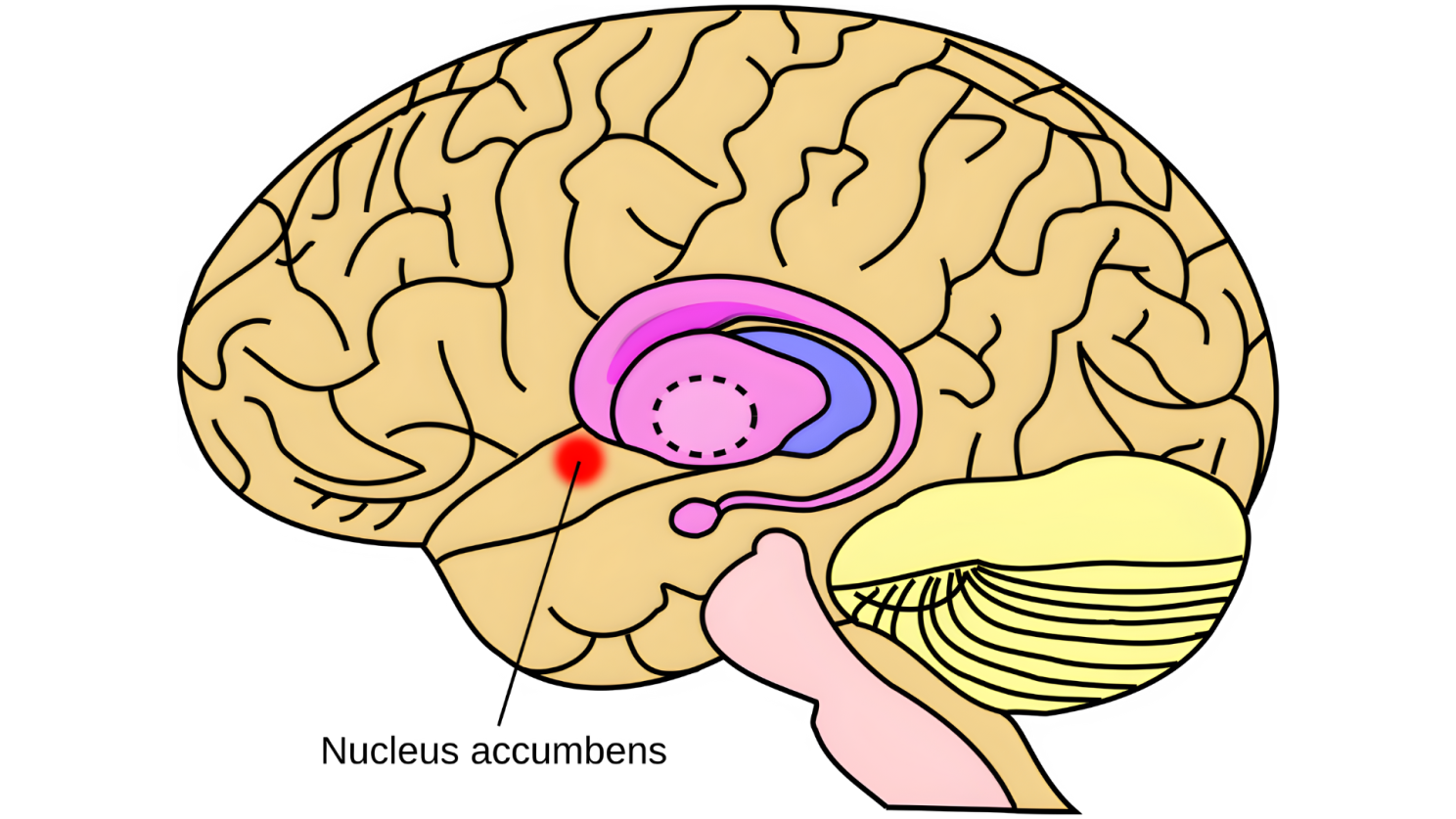

The nucleus accumbens is a small cluster of neurons located at the base of your forebrain, deep in your brain's reward circuitry. For decades, scientists called it the brain's "pleasure center" or "reward center." But that label turned out to be misleading. Research has revealed something far more interesting: this structure doesn't actually generate pleasure. Instead, it drives motivation and creates the sense of wanting something.

Think of the nucleus accumbens as your brain's motivation amplifier. It takes cues from your environment, signals about potential rewards, past experiences, and current needs, then generates that sense of drive that makes you pursue something. When it lights up, you feel compelled to act, to seek, to obtain.

But here's where things get fascinating: the circuits that create this motivational drive are distinct from the neural systems that generate actual pleasure when you consume or experience the reward. Your brain separates "I want that" from "I like that" at a fundamental level.

This discovery initially came as a surprise to researchers. Neuroscientist Kent Berridge and his colleagues were among the first to document this separation in groundbreaking experiments during the early 1990s. In one experiment, neuroscientists found that when they depleted dopamine in rats, the animals lost all motivation to seek food but their facial expressions of pleasure when tasting sugar remained completely normal. The rats still liked the sugar, they just didn't want to go to it anymore.

Further experiments revealed the reverse could also happen. Stimulating dopamine systems made animals intensely pursue rewards and work harder to obtain them, but didn't increase their expressions of enjoyment when actually consuming those rewards. The wanting went up without the liking following along.

In humans, similar patterns can take place. People given drugs that suppress dopamine neurotransmission report feeling less motivated and less interested in pursuing rewards like food or drugs. However, when they actually consume those same rewards, their ratings of how pleasant or enjoyable the experience is remain unchanged. In other words, they feel less driven to seek the reward, but once they have it, they enjoy it just as much as before. The motivation drops, but the pleasure stays constant.

This separation between wanting and liking isn't just an interesting bit of neuroscience. It has profound implications for how you experience life, make decisions, and understand your own behavior.

The Achievement Paradox

Ever noticed how achieving a goal you've worked toward for months or even years sometimes feels anticlimactic? You wanted it so badly, but the actual experience of having it doesn't match that intensity. This is your wanting and liking systems showing their independence. The dopamine-driven wanting system can create enormous motivation to achieve something, while your pleasure systems might respond with a modest "that's nice" when you actually get there.

Think about finally getting that new car you've been dreaming about. For months, you obsess over it, research every detail, imagine yourself driving it. The wanting system is running at full throttle. Then you get it, and for the first week or two, it's exciting. But after a month? It's just your car. The initial thrill fades, and you're already eyeing the next model, the next upgrade, the next thing to chase. The wanting system has already moved on to a new target, while the liking never quite caught up to the intensity of the pursuit.

This explains why some highly successful people feel perpetually unfulfilled. They're excellent at activating their wanting systems and pursuing achievements, but those achievements don't necessarily engage their liking systems in proportion to the effort invested.

The Scrolling Trap

Social media and smartphone apps have become remarkably effective at hijacking the wanting system. Each notification, each pull-to-refresh, each new post triggers a small dopamine response that says "there might be something interesting here." Your brain wants to check, wants to see, wants to engage. But the actual experience of scrolling often provides minimal pleasure. You keep wanting to check your phone without particularly liking what you find when you do.

This mismatch between intense wanting and minimal liking is precisely what makes these behaviors feel compulsive and draining. You're driven to do something that doesn't actually satisfy you, creating a cycle that's hard to break.

Understanding Addiction

The wanting-liking disconnect becomes especially pronounced in addiction. Research shows that repeated drug use can sensitize the brain's wanting systems, making drug-related cues trigger intense urges and motivation. Meanwhile, the actual pleasure derived from the drug often decreases over time as tolerance develops.

This creates a devastating trap: addicts can experience overwhelming wanting for a substance that no longer provides much pleasure. They chase drugs not because the drugs make them feel good, but because their wanting systems have been permanently altered to generate intense motivation whenever they encounter drug-related cues. The wanting persists even when the liking has largely gone away.

This same pattern can emerge with behavioral compulsions. Some people develop intense wanting systems around food, gambling, shopping, drugs, lust, or money, pursuing these activities compulsively even when they derive little actual pleasure from them.

Your nucleus accumbens and its dopamine pathways don't operate in isolation. They respond to cues in your environment, especially cues that have been associated with rewards in the past. Your wanting system can activate when encountering familiar situations, even when recent experiences with those same cues have been disappointing or unrewarding.

These cue-triggered urges happen quickly and often unconsciously. You might suddenly find yourself wanting something before you've even consciously registered what triggered that want. This is why addiction recovery often focuses so heavily on avoiding triggers, the cues associated with past drug use can activate wanting so intensely that conscious intentions to abstain get overwhelmed. Importantly, wanting can be amplified by your current state. Stress, emotional arousal, relevant appetites, or intoxication can all heighten how intensely you want things.

While the wanting system is large and robust, the neural systems that generate actual pleasure are smaller and more fragile. Intense pleasure requires the coordinated activation of specific brain regions, including small "hedonic hotspots" where stimulation can amplify enjoyment.

These pleasure-generating circuits rely on different neurotransmitters than the wanting system, particularly opioid (the brain's natural versions of heroin) rather than dopamine. This is why manipulating dopamine changes motivation but not pleasure, and why opioid drugs like heroin, morphine, and prescription painkillers can intensely affect pleasure experiences.

The fragility of pleasure systems compared to wanting systems might explain why intense desires are more common in daily life than intense pleasures. It's easier to want many things intensely than to deeply enjoy them when obtained.

Knowing that your brain separates wanting from liking can help you craft a life where what you chase and what you actually enjoy are better aligned. Here’s how to put this into practice:

Audit Your Pursuits: Your nucleus accumbens is a master at chasing signals. Ask yourself what you're running after right now. When you’ve achieved similar goals in the past, did the “high” last, or did it fade quickly? This kind of brain audit helps separate goals that bring true satisfaction from ones that only feed your wanting drive.

Spot Dopamine Loops: Notice when your wanting system has gone rogue, pushing you to repeat behaviors that don't make you happier.

Prioritize Real Pleasure Your liking system is quieter and more fragile, but many times it’s the part that actually fuels joy/peace. Protect time for activities that consistently light it up such as a workout, cooking, music, work that you enjoy, or spending time with loved ones. These may not carry the loud dopamine rush of chasing something new, but they deliver deeper, steadier rewards.

Hack Your Cues The nucleus accumbens is highly cue-driven. Instead of relying on willpower, reshape your environment:

When you change the cues you change what your wanting system locks onto, and that makes it much easier for your liking system to catch up.

The nucleus accumbens and the wanting-liking distinction reveal something profound about human nature. Many times we aren't pursuing things that make us happy. We're often pursuing what our brains have been conditioned to want, influenced by past associations, environmental cues, our current emotional state, and countless other factors.

This doesn't mean motivation is bad or wanting is wrong. It helps you pursue important goals, overcome obstacles, work for delayed rewards, and navigate complex environments. The problem emerges when wanting becomes disconnected from genuine satisfaction, when you're driven to pursue things that don't actually enhance your life.

By understanding this separation between motivation and pleasure, you can make more conscious choices. You can notice when you're being driven by empty wanting versus pursuing something genuinely rewarding. You can create a life where what you chase and what you enjoy are more closely aligned.

More Info: At WellPro, we’re building an AI-native clinical platform purpose-built to scale the next era of care: personalized, preventative, and data-driven. Our thesis is simple but bold; the future of care delivery will be patient-centered, proactive, longitudinal, and closed-loop. That demands infrastructure that can ingest multi-modal health data, generate insight, drive action, and continuously optimize based on outcomes.

We believe Agentic AI is central to making this vision real. Not just chat interfaces or “co-pilots,” but deeply embedded, goal-driven AI agents that operate within the clinical system itself, helping surface insights at the point of care, automate routine tasks, and ensure closed-loop follow-through on interventions.