You might have heard of the vagus nerve: the major nerve that regulates stress and connects your brain to your organs. But there's another cranial nerve with profound influence that rarely gets attention: the trigeminal nerve. This nerve controls all sensation in your face, powers the muscles you use to chew, and connects directly to your brainstem's stress and pain centers.

The trigeminal nerve is why jaw clenching is one of the first physical responses to stress. It's why tension headaches often start at the temples or jaw. It's why TMJ disorders can affect not just your jaw but your sleep, your stress levels, and your overall wellbeing. And here's what makes this nerve particularly interesting: it creates a bidirectional feedback loop between your face and your emotional state. When you're stressed, your face tenses, but that facial tension also signals stress back to your brain through the trigeminal nerve. This is why relaxing your jaw, softening your facial expression, or even forcing a smile can actually change how you feel. Understanding the trigeminal nerve reveals a powerful tool for managing stress that's always available: your face.

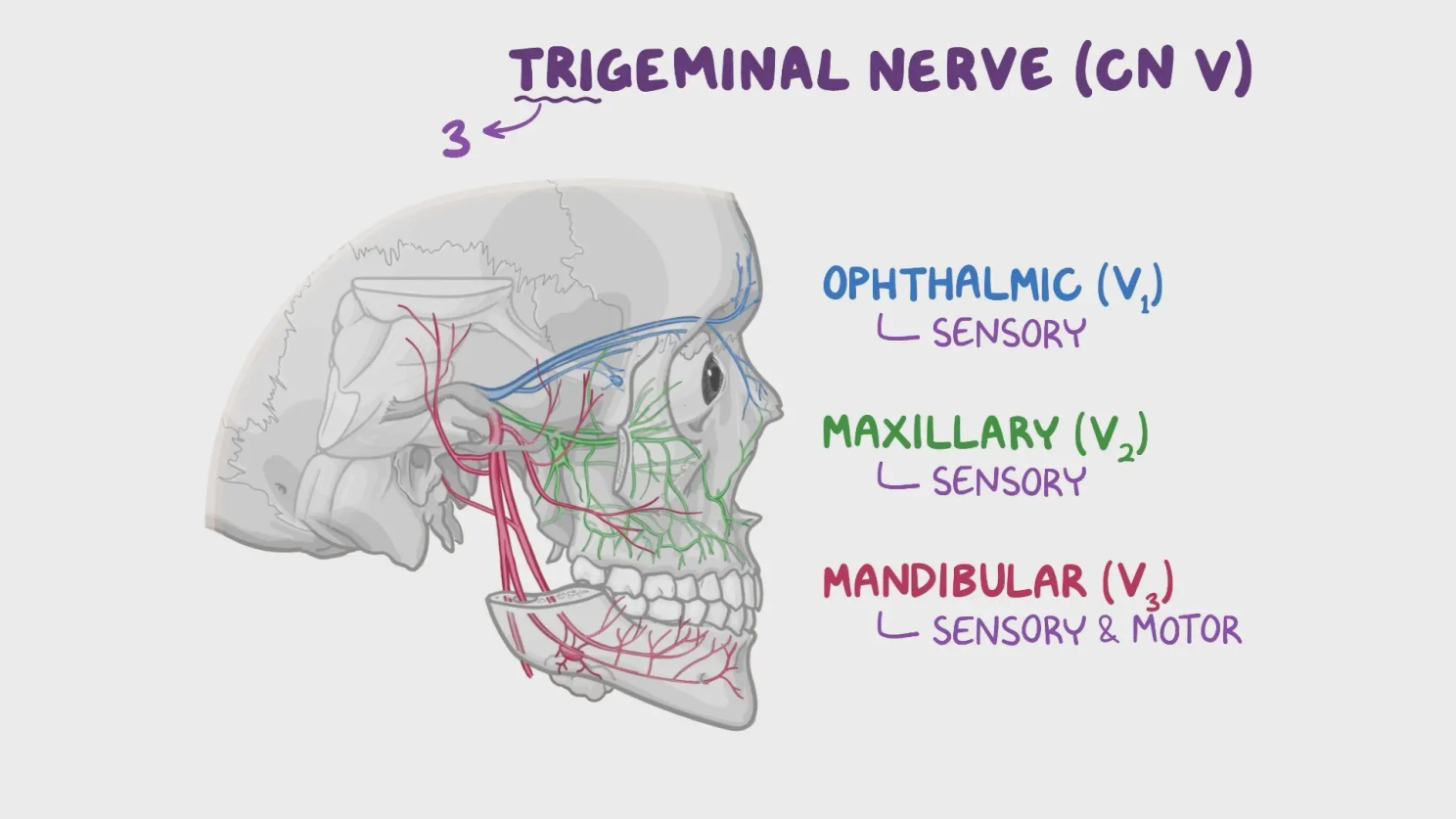

The trigeminal nerve is the fifth and largest of your twelve cranial nerves. Its name comes from "tri" (three) and "geminus" (twin), referring to its three major branches that split into pairs on each side of your face. These three branches cover your entire face in distinct zones.

The ophthalmic branch serves your forehead, upper eyelids, and front of your scalp. The maxillary branch covers your cheeks, upper lip, upper teeth, and sides of your nose. The mandibular branch controls your lower lip, lower teeth, jaw, and parts of your ear. Together, these branches create a complete sensory map of your face, transmitting every touch, temperature change, and pain signal to your brainstem.

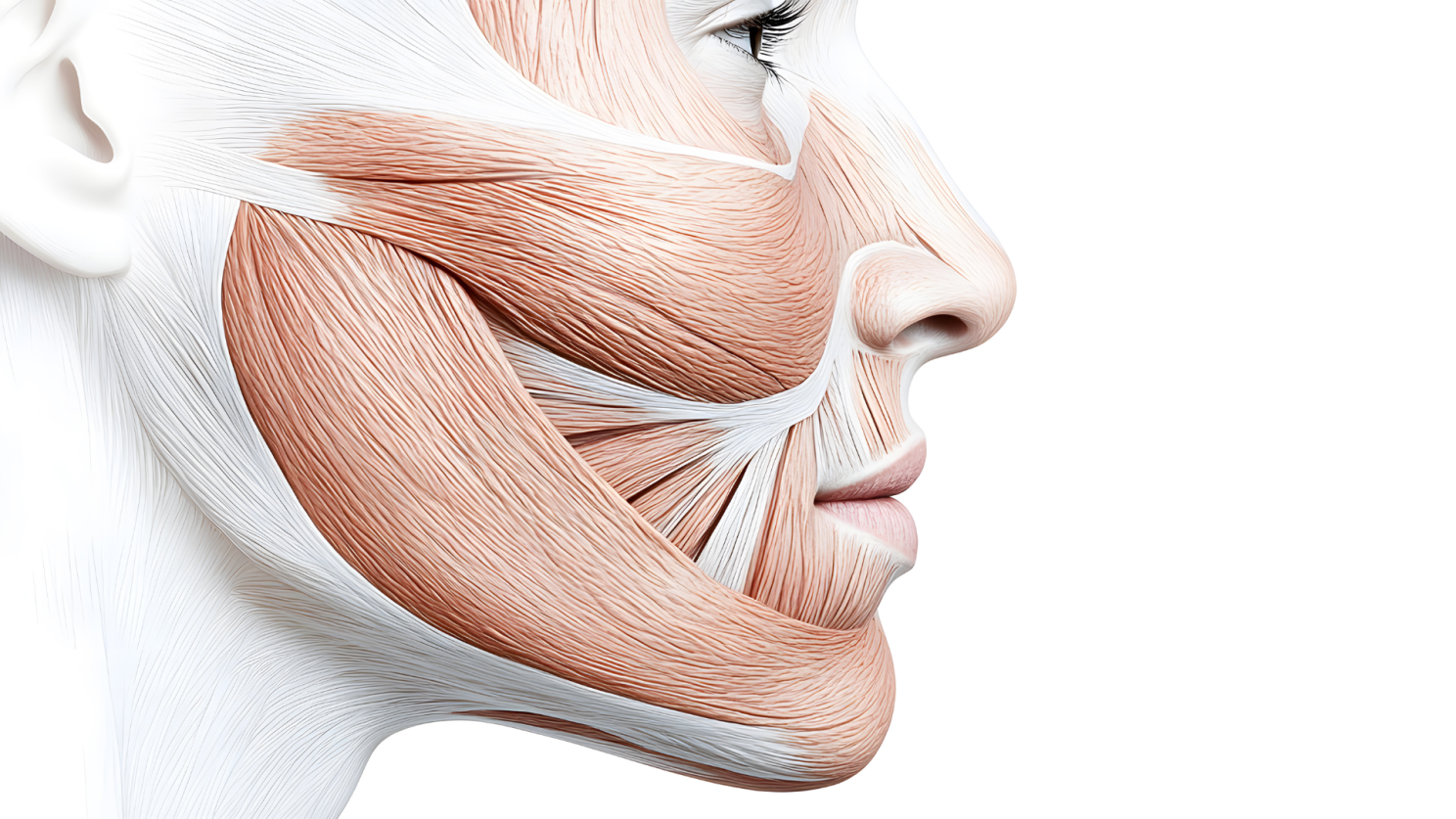

Unlike purely sensory nerves, the trigeminal nerve also has motor functions. The mandibular branch controls the muscles you use for chewing (the masseter, temporalis, and pterygoid muscles). This dual role means the trigeminal nerve both feels your face and moves your jaw, which creates unique opportunities for both problems and solutions.

The trigeminal nerve doesn't just send signals to sensory processing areas. It has direct connections to several critical brain regions including the trigeminal nucleus in your brainstem, which connects to areas that process pain, regulate stress, and control emotional responses.

When you experience stress, your nervous system activates a protective response that includes muscle tension. The trigeminal nerve controls some of the strongest muscles in your body (your jaw muscles), and these muscles are among the first to tense during stress. This isn't just correlation. The pathway is direct: stress signals travel to the trigeminal motor nucleus, which activates jaw muscles, creating the clenching response you might have experienced during anxiety or concentration.

But here's where the feedback loop begins: when those jaw muscles clench, they send signals back through the trigeminal nerve to your brainstem. These tension signals get interpreted as threat indicators, only making your stress response worse. The tighter your jaw, the more stress signals your brain receives, which can increase overall tension and anxiety. This bidirectional communication explains why chronic jaw clenching doesn't just hurt... it actively perpetuates stress.

The trigeminal nerve is the primary pathway for facial pain, which is why so many head and face pain conditions involve this nerve. Tension headaches often originate from sustained contraction of muscles controlled or sensed by the trigeminal nerve. When your temporalis muscles (your temples, the muscles on the sides of your head) or masseter muscles (your jaw muscles, the primary muscles used for chewing) stay contracted for extended periods, they create pain signals that travel through the trigeminal nerve.

Migraines have a particularly strong connection to the trigeminal nerve. During a migraine, the trigeminal nerve becomes sensitized and can release inflammatory substances that dilate blood vessels and create the throbbing pain characteristic of migraines. This is why many migraine medications target the trigeminal system specifically.

TMJ disorders (temporomandibular joint dysfunction) involve problems with the jaw joint and surrounding muscles, all of which are innervated by the trigeminal nerve. TMJ can cause jaw pain, difficulty chewing, clicking sounds, and even ear pain. Because the trigeminal nerve connects to stress centers, TMJ disorders often worsen during periods of stress and can contribute to overall anxiety and sleep disruption.

Trigeminal neuralgia is a more severe condition involving the trigeminal nerve itself, causing sudden, severe facial pain triggered by ordinary activities like eating, talking, or touching your face. This demonstrates how sensitive and powerful the trigeminal nerve's pain pathways can be.

Here's one of the most fascinating aspects of the trigeminal nerve: the relationship between your facial expressions and your emotional state isn't one-way. Most people understand that emotions create facial expressions. When you're happy, you smile. When you're stressed, your jaw might be tight and your brow furrowed. But research has demonstrated that this relationship also works in reverse through a phenomenon called the facial feedback hypothesis.

When you create a facial expression, the muscles involved send signals through the trigeminal nerve (and other cranial nerves) back to your brain. These signals don't just report "muscles are contracting." They influence the emotional centers that process how you feel. Studies have shown that people who hold a smile (even artificially) report feeling happier and show lower stress responses than people who hold neutral expressions. Conversely, people whose frown muscles are paralyzed (through Botox, for instance) report experiencing less intense negative emotions.

The mechanism involves the trigeminal nerve transmitting information about muscle tension and facial configuration to your brainstem, which then communicates with regions like the amygdala (emotional processing) and hypothalamus (stress response). When your facial muscles signal "relaxed" or "smiling," your brain interprets this as a safe state and adjusts your stress response accordingly. When your facial muscles signal "tense" or "frowning," your brain interprets potential threat and maintains alertness.

Understanding the trigeminal nerve reveals several practical strategies for managing facial tension, reducing pain, and regulating your stress response through your face.

Progressive Jaw Relaxation: Throughout your day, check in with your jaw. Are your teeth touching? They shouldn't be unless you're actively chewing. The resting position for your jaw should have your lips closed but teeth slightly apart with your tongue resting gently on the roof of your mouth. Practice consciously relaxing your jaw muscles, especially during stressful moments.

Facial Massage: Massaging the muscles along your jaw (masseter), temples (temporalis), and forehead can release chronic tension and reduce pain signals traveling through the trigeminal nerve. Use gentle circular motions with moderate pressure.

Intentional Facial Expressions: Since facial expressions can influence emotional state through the trigeminal nerve, consciously softening your facial expression during stress can help regulate your nervous system. This doesn't mean forcing happiness, but rather releasing unnecessary tension in your face (unclenching your jaw, relaxing your forehead, softening around your eyes). Do a quick scan of your face and notice if you're holding tension anywhere, then consciously release it.

Breathing Through Your Nose: Nasal breathing naturally promotes a more relaxed jaw position than mouth breathing. Proper tongue posture (tongue resting on the roof of your mouth) also supports jaw relaxation and optimal trigeminal nerve function.

Manage Stress Systemically: Since stress can activate jaw clenching through the trigeminal nerve, addressing stress through exercise, sleep, and stress management practices reduces the upstream signal that causes facial tension.

Address Dental Issues: Misaligned bite, missing teeth, or dental problems can create chronic abnormal stimulation of the trigeminal nerve. Working with a dentist to address these issues can reduce ongoing nerve irritation.

Heat or Cold Therapy: Applying warmth to tense jaw muscles or cold to inflamed areas can modulate pain signals traveling through the trigeminal nerve and reduce muscle tension.

Breathwork and Meditation: Practices like meditation and breathwork help you develop awareness of where you're holding tension in your body, including your face. This increased body awareness makes it easier to notice and release facial tension throughout your day, interrupting the stress feedback loop through the trigeminal nerve.

The trigeminal nerve creates a powerful feedback loop between your face and your brain. While this loop can potentially lead to perpetual stress, it also provides a direct way to influence your nervous system state. This means you have a tool for stress regulation that's always available: your facial muscles. Consciously relaxing your jaw, releasing tension in your temples, and softening your facial expression send calming signals through the trigeminal nerve to your brainstem. These aren't just comfort measures; they're active interventions in your stress response system.

The trigeminal nerve demonstrates how interconnected your physical and emotional states are. The tension you hold in your face doesn't just reflect your inner state, but actively influences it. Understanding this nerve reveals that managing facial tension isn't about appearance or comfort alone. It's about regulating the signals constantly traveling between your face and your brain, influencing your stress levels, pain perception, and emotional wellbeing. Your face is more than just an expression of what you feel. It's a powerful tool for shaping how you feel.